Iron and steel – The history of the Henrichshütte Hattingen ironworks

In 1854, ore, coal, and a river attracted a nobleman from the Harz Mountains to found a company in the Ruhr region. For 150 years, iron and steel were produced, cast, forged, and rolled at the smelting works named after him.

Rails and wheel sets for the railway, large forged and cast parts, turbine shafts and nuclear reactors, armour plating and grenades, as well as parts for the space industry were produced in Hattingen. The history of the Henrichshütte is exemplary for the emergence, development and decline of heavy industry in the Ruhr area.

1854–1900: From founding to the first crisis

By 1850, the Ruhr Valley was already an industrialized area. Numerous coal mines produced hard coal, which was transported to the Rhine on the Ruhr River, which had been made navigable in 1780. With the discovery of iron ore deposits near Hattingen by Friedrich Hellmich, favorable conditions arose for the establishment of modern ironworks.

Count Henrich von Stolberg-Wernigerode also recognized this. His family had been operating an iron foundry in Ilsenburg since the 16th century – initially with the help of experts from the Siegerland region. Now the migration was repeating itself in the opposite direction: ironworkers from the Harz region came to the Ruhr to smelt iron on behalf of the count.

Carl Roth, the first master smelter, used advanced Belgian technology to build the blast furnaces. It was probably also him who suggested naming the new plant after his client, who had died in February 1854. Despite several changes of ownership, the name Henrichshütte remained with the company until it was shut down.

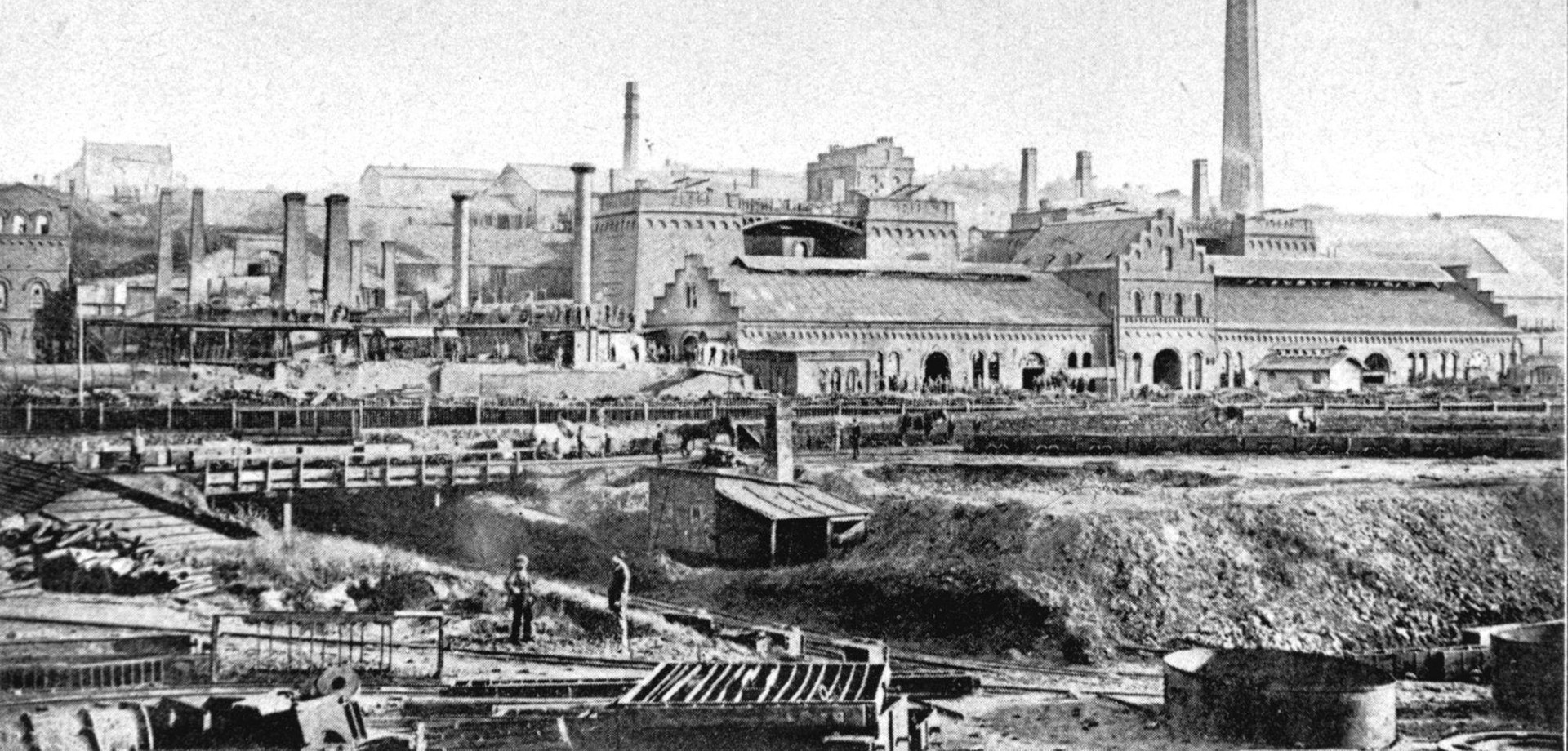

As early as 1857, the Henrichshütte was sold to the Berliner Discontogesellschaft. The Berlin banking house initially invested in further expansion: in addition to four blast furnaces, coking plants and foundries, rolling mills and machining workshops were built. One of the last major construction projects was the construction of a modern Bessemer steelworks in 1872, now the oldest building on the grounds of the industrial museum. Shortly afterwards, the Henrichshütte was incorporated into the Dortmund Union for Mining, Iron, and Steel Industry. The associated loss of independence and integration into higher-level corporate structures, combined with the founding crisis that broke out in 1873, led to drastic changes in Hattingen: rail and river steel production had to be transferred to Dortmund – including the Bessemer steelworks, which had only just gone into operation. A period of stagnation began for the Henrichshütte.

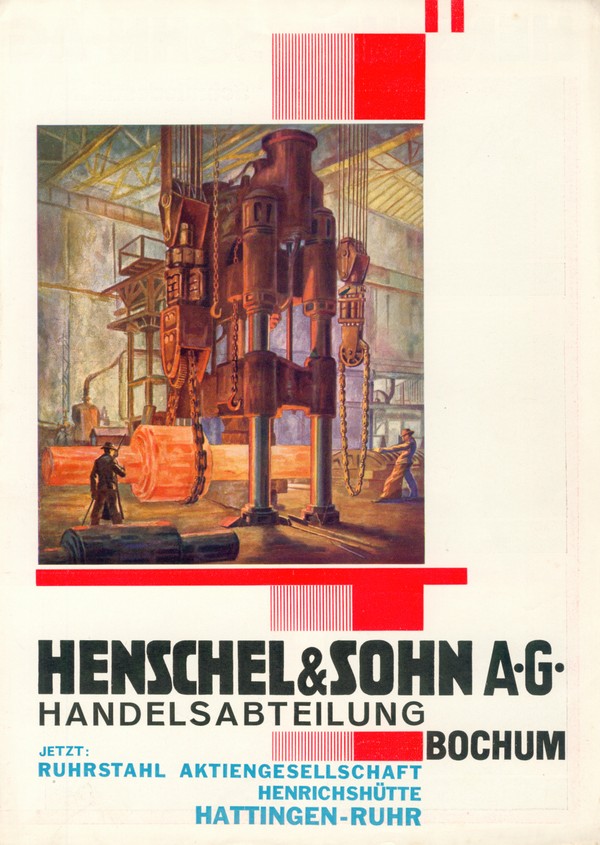

1900 to 1930: Upswing under Henschel

In February 1904, the Kassel-based locomotive and machine factory Henschel & Sohn purchased the Henrichshütte. Within a few years, the smelter was completely modernized with enormous capital investment. The material bunkers for the new blast furnaces and the gas center, which were driven into the hillside, date from this period. However, the modern gas engines not only generated the hot blast required for blast furnace operation, but also electrical energy.

Before World War I, new and modern facilities sprang up all over the site: a coking plant, a rolling mill, a pressing and hammering plant, foundries, and machining workshops. The modernization of the ironworks was accompanied by an expansion of the product range. Sheet metal and pipes for locomotive construction were produced in Hattingen and further processed in Kassel, as were the wheel sets produced at the Henrichshütte.

However, the new factory facilities also allowed for larger dimensions: as early as 1907, steel castings weighing up to 50 tons were available for locomotive, machine, and shipbuilding, including roller stands, steam hammer parts, ship stems, ship propellers, rudders, and anchors. The forge and machining workshop supplied ship shafts, crankshafts, turbine shafts, and rollers. With the realignment and specialization of the smelting works, Henschel laid a solid foundation for the future. After the outbreak of World War I, the modern and efficient smelting works became part of the German Empire's “arms factory” for the first time. Until the end of the war, grenades, gun barrels, and special sheet metal were manufactured.

The end of the war in 1918 was followed by turbulent times. The continuing demand for railway equipment facilitated the return to peacetime production. In 1923, inflation and the occupation of the Ruhr led to the temporary closure of the steelworks, and the following years brought no economic improvement, so that Henschel finally parted ways with the Henrichshütte.

1930 to 1945: Armor plates and gun barrels for the war

In 1930, the Henrichshütte was sold to Vereinigte Stahlwerke and incorporated into the newly founded Ruhrstahl AG. Nevertheless, the future of the Henrichshütte seemed far from secure, and just two years later, there was even talk of closing it down. By April 1933, only 1,492 people were still working at the steelworks – fewer than in 1905. In the wake of National Socialist economic policy and the start of arms production, the number of workers rose steadily in the 1930s. Once again, the Henrichshütte supplied high-quality steel for tank armor and gun barrels, and in 1939, it began manufacturing tank hulls for the Wehrmacht. The almost complete switch to arms production again required extensive expansion and modernization. The measures included the construction of blast furnace 3, which was fired up on October 10, 1940, and today forms the centerpiece of the LWL Industrial Museum.

Shortly before, in August 1940, the first French prisoners of war had arrived at the Henrichshütte to perform forced labor in arms production. They were followed by Dutch, Belgian, Russian, and Italian prisoners, who were housed in a total of 14 camps. Hard labor, poor hygienic conditions, and insufficient food supplies, coupled with the constant threat of harassment and punishment, characterized the lives of these people.

With the establishment of a Gestapo detention camp in 1943, everyday terror took on a new dimension. Here, people were imprisoned under the harshest conditions and subjected to brutal treatment, and forced to work at the steelworks. By the end of the war, 36 people had died here – the actual number of victims is likely to be much higher.

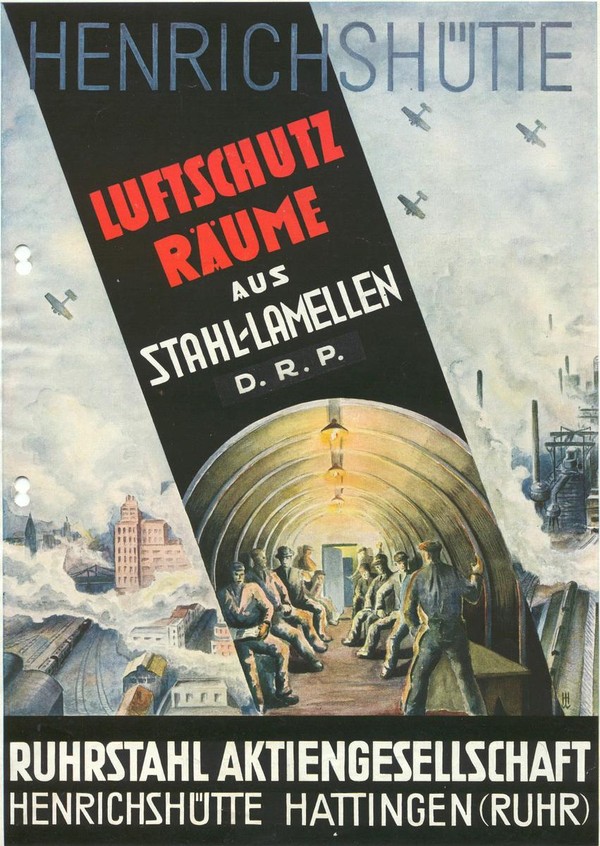

The Henrichshütte was not unprepared for the increasing air raids in the final years of the war. Towards the end of the war, there was an extensive system of bunkers and air-raid shelters, underground passageways, and observation posts on the site. When American troops liberated Hattingen on April 16, 1945, a third of the factory facilities had been destroyed.

A new beginning after 1945

After the end of the war, the British military government initially granted Henrichshütte a limited operating license. This initially secured the plant's existence. The shock was all the greater when Henrichshütte was placed on the dismantling list in October 1947. The impending dismantling of the steelworks, steel foundry, and heavy plate rolling mill would inevitably have meant the end of the site.

The tough negotiations dragged on for over two years. It was not until 1949 that the dismantling of the facilities was finally averted. At the same time, the demerger of the German iron and steel industry in 1951 led to the founding of a new Ruhrstahl AG based in Hattingen. The rebuilding process could begin.

Once again, in view of the rising demand for steel, the company relied on the concept of an integrated steelworks. The close integration of blast furnace operations, steelworks, foundries, forges, and machining workshops enabled the production of a wide range of products, from special sheet metal to crankshafts. By focusing on quality products and large workpieces, the mill remained competitive for many years within the corporate structures of Ruhrstahl and, from 1963, Rheinische Stahlwerke, even though the limited space available on the factory premises, which were confined by the Ruhr, could be considered a negative location factor, as could the poor transport links.

These disadvantages, which were countered to a limited extent in 1960 by the relocation of the Ruhr and the resulting expansion of the site, were offset by products that could hardly be manufactured anywhere else in the West German metallurgical industry. In addition to large castings and forgings, it was special-purpose products such as the first nuclear reactor for the Gundremmingen nuclear power plant, which was manufactured entirely in Hattingen, that secured the future of the Hattingen plant.

Modernization

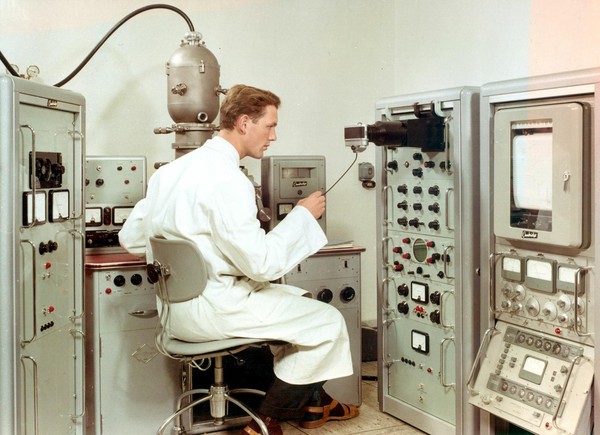

New analysis methods ensured product quality. Specialization in high-quality steels and the need to respond to specific demands and requirements necessitated corresponding research in the field of secondary metallurgy. One result was the “Ruhrstahl-Heraeus process” for the vacuum treatment of molten steel, which was developed at the Henrichshütte in 1958 and is now widely used.

The ongoing modernization and rationalization of the plants changed the work at the steelworks. In many areas, the individual experience of the steelworkers gave way to modern process control. This was evident, for example, in the reorganization of steel production: the continuous casting plant, which went into operation in 1967, eliminated several production steps in the previous slab production process and, as an important link between the steelworks and the rolling mill, brought about a significant rationalization push. Three years later, the commissioning of the new open-hearth furnace ended the era of Siemens-Martin furnaces, which had been producing steel at the mill since 1904. With the commissioning of the electric steel mill, this modernization process was completed in 1976.

1974 to 1987: The Decline

In 1974, Henrichshütte became part of the Thyssen Group. In the same year, German crude steel production peaked at 53 million tons, only to collapse immediately afterwards. In 1983, the first plants in Hattingen were also shut down. While 8,800 people were still working at Henrichshütte in 1974, twelve years later there were only 4,800.

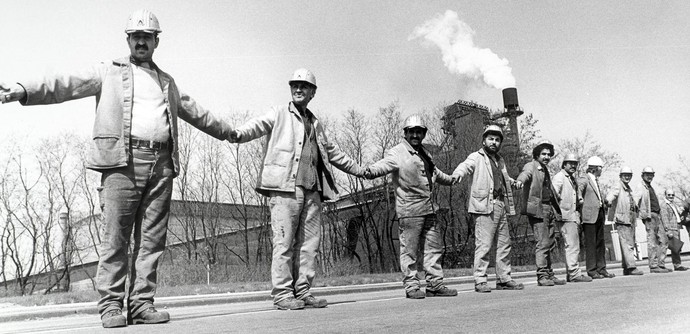

At the beginning of 1987, Thyssen Stahl AG announced the closure of the blast furnaces, the 4.2 m heavy plate mill, the electric steelworks, and the continuous casting plant, as well as the discontinuation of training operations at the Henrichshütte. This meant the imminent demise of the steelworks and the loss of almost 3,000 jobs and the majority of the apprenticeships available in Hattingen. When the closure plans became known, a protest movement emerged, supported by all sections of the Hattingen population, which drew attention to the impending closure and loss of jobs in imaginative and varied ways. The actions of the “steelworks struggle” ranged from a demonstration with 30,000 participants to the establishment of a “village of resistance” to a human chain surrounding the steelworks site and a hunger strike by women. They generated public attention and led to socially acceptable solutions for the job cuts, but did not prevent the end of the Henrichshütte steelworks.

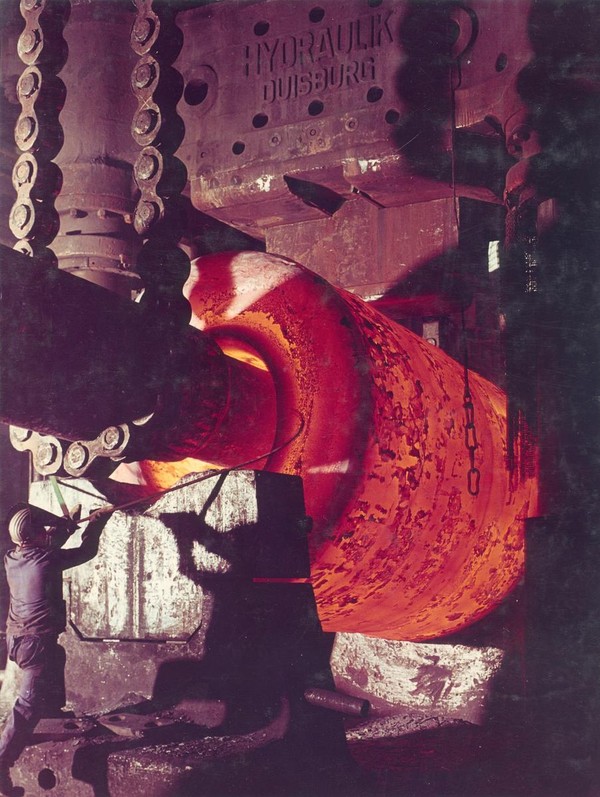

With the last tapping on December 18, 1987, pig iron production in Hattingen came to an end after 133 years. With the closure of the blast furnaces and rolling mill, the advantages of an integrated steelworks, developed and proven over decades, were lost. The takeover of the blast furnace, forge, and machining workshops by the newly founded Vereinigte Schmiedewerke Gesellschaft in 1988 brought only a brief reprieve. In 2004, the forge was the last fire-based operation to close.